OUR RESEARCH

Studies of viral evolution

Our studies of viral evolution focus on a number of viruses that have naturally switched from one host to another, so that we can study their evolution in nature in the different hosts, as well as in tissue culture model systems of the viral evolution and selection. We have focused on receptors (TfR and sialic acids) and antibody in some of our work, as the binding sites for those vary naturally in the viruses.

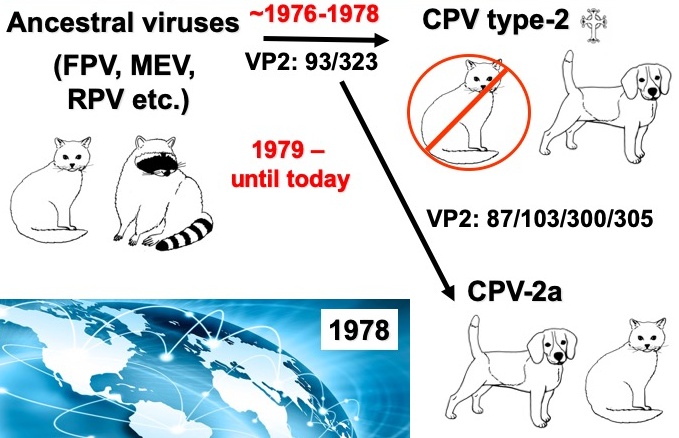

Evolution of canine parvovirus (CPV) and feline panleukopenia virus (FPV).

CPV emerged in 1978 when it spread world-wide in a pandemic of disease in dogs. The diseases seen were diarrhea in dogs older than a few months of age, and sudden death due to myocarditis (damage to the heart muscle) after infection of very young puppies. The virus was also isolated in cell culture in 1978 and soon recognized as a parvovirus that was similar to the FPV that had long infected cats and related carnivores. The CPV sequences showed that the virus in dogs was >98% identical to the FPV, with only a few key mutations in the genome that were associated with the canine viruses. Early studies using recombination mapping showed that the canine host range was due to a small number of changes in the capsid protein gene – the overlapping genomic region that encodes the VP1 and VP2 proteins. Since the CPV emerged we have followed the evolution of the virus, and see that there there was an initial global spread of a variant virus (called CPV-2a), and since then the virus has continued to vary slowly in sequence, with about one new viral mutation becoming fixed or widespread each year.

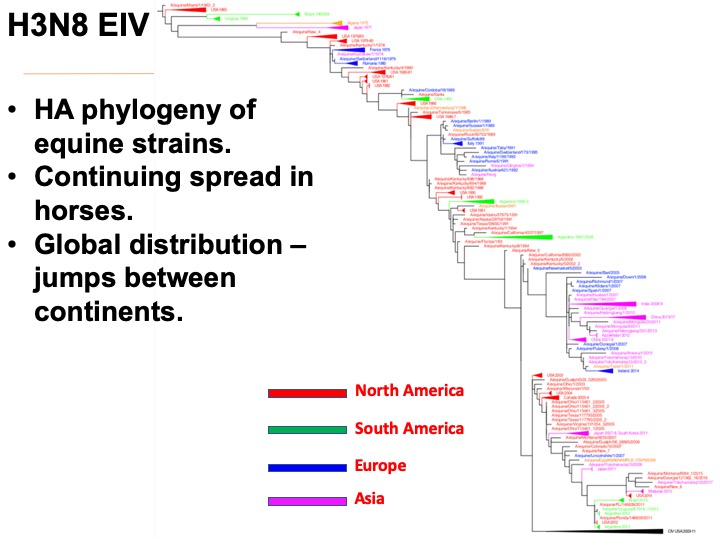

Evolution of the H3N8 canine and equine influenza viruses.

Canine influenza virus. The H3N8 CIV was first recognized in dogs around 2003 and 2004, in particular when it caused severe disease in greyhounds in Florida and in many other states where greyhound racing was carried out. After control measures were introduced into the greyhound population, the main sites of virus spread were in Colorado and in the North East US states. By 2012 the virus had died out in Colorado, and for the next four years the virus was seen in the New York where it circulated, as well as in nearby states which suffered short outbreaks that died out. Examining the sequences of the H3N8 CIVs showed that there were distinct clades that represented the viruses from Colorado, and those from New York or nearby states. There was clearly one population in New York that appeared to be carried by infected dogs to nearby states. The virus was being maintained in large animal shelters with many dogs, and it died out when in smaller shelters or in household dogs, likely due to lack of transmission to susceptible dogs. It appears that the virus died out in New York around 2016.

Equine influenza virus. In contrast to the CIV which died out naturally, the H3N8 EIV in horses has spread widely since at least 1963 when it was first recognized in horses in Florida, USA, and the virus most likely emerged originally in South America – perhaps Uruguay or Argentina. The virus has continued to spread around the world, and has been evolving at a more-or-less steady rate since 1963, and there is also evidence for antigenic drift in the horse viruses.

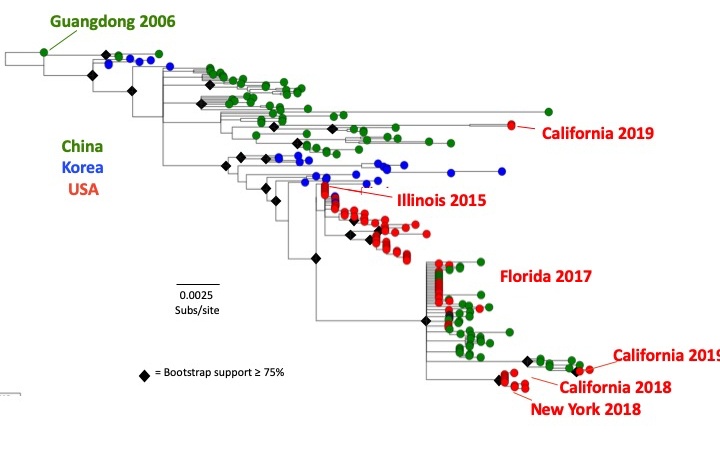

Evolution of the H3N2 canine influenza virus.

The H3N2 CIV appears to have first emerged in dogs in China and Korea around 2005 or 2006, most likely due to an avian influenza virus transferring into the new host. After that time the virus appeared to continue to ciculate among dogs in those countries. The H3N2 CIV was first introduced into the USA in February 2015 and it caused widespread outbreaks in different areas of the the country, as well causing outbreaks in Canada. In the USA the virus has shown strong geographic clustering, with outbreaks in different cities where is a rapid spread, but then with the virus tending to die out after a month or less. Overall there are transfers between different regions of the world – however, most of the US and Canadian outbreaks have been associated with transfers from Korea or China.

Polymerase Mutant Host Cells and Variants.

While DNA viruses also show variation and undergo evolution, the mechanisms behind these processes are much less well understood. Here we use new approaches to vary the rates of mutation of parvoviruses by altering the host cell polymerases – by over-expressing a highly mutagenic form of DNA polymerase δ, or by the translesional polymerases η and κ. Virus derived from infectious plasmids were grown in wildtype feline or human cells, or in cells with the mutant polymerases. Those are being passaged in cells with different polymerases.